EXCLUSIVE| 'Our Black Girls': LA journalist tells stories of forgotten missing women

The stress for the family of someone who goes missing is overwhelming. There is terror, there is despair, but there is also hope. They hope their loved ones will come back to them at the end of the day.

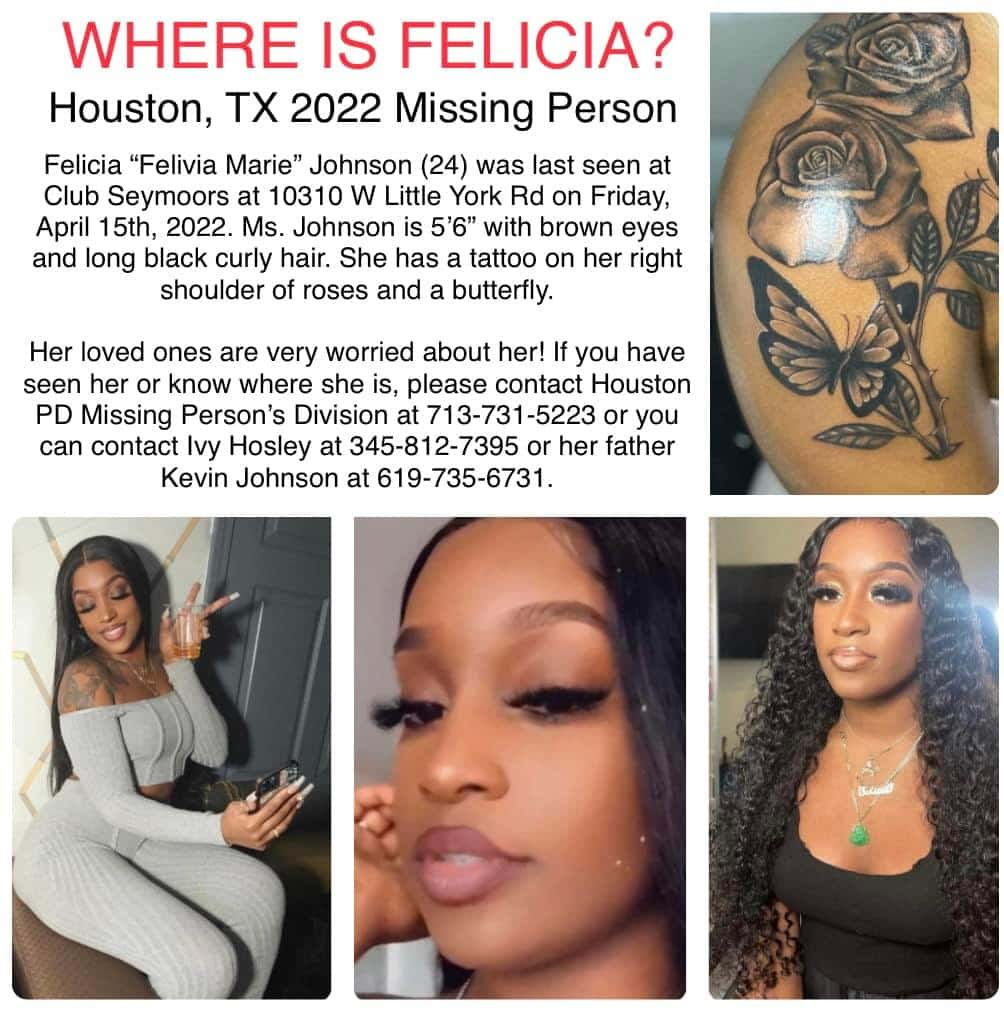

Hoping for the best, the family of 24-year-old Felicia Marie Johnson of Houston issued a public plea for information after she went missing. She was last seen on April 15 when she stopped into the Cover Girls Night Club to look for work. Community activist Quanell X has claimed that Johnson was offered a ride by an unidentified customer after her Uber was late. No one has since heard from Johnson.

READ MORE

Madeleine McCann case: Convicted rapist Christian Brueckner named ‘formal suspect’

Dead Arapaho women's sister slams color bias in media coverage of missing persons

Felicia has been missing for a month now. A private investigator hired by Felicia's family reportedly found her blood-covered phone. While Houston police said they are actively investigating the case, nonprofit search-and-rescue group Texas EquuSearch has also joined in to search for Johnson.

A few months ago, the story of missing Gabby Petito captivated the media and the public. The 22-year-old's body was tragically found within eight days of being reported missing by her family. For Black families, however, Gabby's story was a reminder that the media is not always equally concerned about their missing daughters. There would be an occasional update, but no evening news special. Their stories will gradually fade and the families will continue their search alone. This is not something only Black families claim, but also data.

According to the National Crime Information Center, 268,884 women were reported missing in 2020. Nearly 100,000 of them were Black women and girls. Black women reportedly account for less than 15% of the US population, and yet, they made up more than one-third of all missing women reported in 2020.

And here's why we do not know their names: In a 2016 study titled 'Missing White Women Syndrome', legal scholar Zach Sommers found that the media covers news of missing Black people with fewer stories compared to when people from other demographic groups go missing. Will families of Black women continue to grieve alone as the stories of their daughters fade away?

Keeping in mind this issue plaguing society, Erika Marie Rivers, 39, launched a website called 'OurBlackGirls' (OBG). A journalist and activist for several years, Erika lives in Los Angeles. She launched the site back in 2018, and calls it her "passion project". OBG became a trademarked, non-profit organization in 2021. Through her website, Erika has been telling stories of as many of these Black women as possible. Her website focuses on stories of Black girls and women, many of which have not been spoken about very often. It lists Black women who have been missing or found dead.

'Our Black Girls'

Erika says that her interest in bringing stories of these Black women and girls to the fore does not stem from some sort of morbidity, but a sense of familiarity. "I was looking at faces that were similar to mine and that made me identify with these victims or survivors. I would think about their families, their loved ones whose hearts ached while these women were missing, who were angered by them being mistreated, or who mourned because they were murdered," she says on OBG's website.

Erika believes that the stories she reports on are "more than the highlight clip on the ten o’clock news." "These are and were our sisters, many of whom endured deception and/or violence. We shouldn’t sweep their stories under the rug and move on to the next hot topic," she adds on the website. OBG also has an active Instagram page.

"We as a collective media culture need to be more sensitive"

"In American media, racial and ethnic biases are the norm. It’s so embedded in our culture that the public is desensitized to the inequalities in coverage. When it is called out or becomes an issue, it’s easy to receive pushback from people who would rather seek out stereotypes about marginalized communities than joining the fight for equity," Erika told MEAWW. "OurBlackGirls is about shining a light on these stories of missing and murdered Black women who are, just for existing, deserving of attention—as are their families who often go ignored by mainstream media."

Talking about Felicia Johnson's case, Erika said, "Felicia’s case was sent to me early on, maybe a day or two after she went missing, and since the time, the public has made sure that information circulates. I think it’s important for us to remain consistent and not just treat cases as news cycles. We get caught up in feeling the need to share and post as soon as something occurs, which is needed, but even after the hype dissipates, many of these cases still exist."

"Also, it’s my belief that we as a collective media culture need to be more sensitive within the true crime community in how we post, share, and talk about cases. These are real people with real families going through real trauma, so adding speculative information or victim-blaming isn’t helping anyone," she added.

The story that stayed with Erika

Felicia's case is one of the latest among thousands of disappearances over the years. OBG has listed stories of Black women from decades ago. There is the story of missing Michelle Chrysler, 22, who was last seen with an unknown man in 1997. The website also talks about Sonya Tukes, 22, who reportedly went to bed and disappeared by the morning back in 2004. Cellastine Wade, 18, has been missing from New Jersey since 1968.

Asked if there is one case in particular that affected her significantly, Erika said it is the 1989 disappearance of 15-year-old Monica Bennett. "Monica and her 13-year-old brother disappeared together and it was widely suspected that their stepfather had something to do with it. Monica was failed by nearly every adult in her life—her stepfather was sexually abusing her and her sisters, and her mother knew but didn’t believe her and stayed with him. Monica’s school and the police were alerted but her mother told them she was lying for attention, so they did nothing. It would take the mother walking in on the abuse to break up with her husband, but she then forced Monica and her brother to help the stepfather move. They vanished that same evening and after disappearing, their mother reconciled with the stepfather, and they moved their family to another state," Erika said.

"Until the 2000s, Monica and her brother were classified as runaways and the police didn’t take the case seriously. They were seen as Black teens who probably left home because they didn’t like their stepfather, but now, foul play is suspected. It is unthinkable to know that a man who was an abuser went on to live a life with the children he abused because the system wouldn’t protect Black children," she added.

Erika's research

Talking of her research, Erika said, "I usually begin with government databases and work from there. Sometimes I turn to other organizations or foundations and I regularly receive cases from OBG supporters hoping to shed light on local news stories or cold cases from their areas. I work as an entertainment/music journalist from 4:00 pm to 12:00 am, and then until about 3:30 am to 4:00 am. I’m researching and answering emails for OurBlackGirls. During the day, I spend hours prepping for work and answering inquiries on OBG’s social media pages as well as sharing posts from other outlets like Black Femicide, Black Girl Gone, Black Is Cold, Black & Missing Foundation, and others who are on the frontlines of this cause."

Asked whether she has ever met families of missing women, Erika said, "I have never met anyone in person but I have corresponded with several families. Many of them reached out after seeing my posts on OBG, while others heard of OBG and requested that I write articles about their loved ones. From women and children who have been missing for decades to unsolved murders, these relatives have been so amazing in not only how they have coped with their tragedies but how they have managed to share their stories with such candor."

"I’ve sat on the phone for hours with people who were just children when their mothers disappeared, or parents who are still searching for answers. It is a privilege to be entrusted with these personal accounts and details, so it is my priority to be sensitive to their experiences," she added.

Erika works a full-time job that occupies a significant amount of her time. She says that despite her best effort at throwing light on cases of missing Black women and trying to advertise on social media platforms, she is often rejected and told that cases of missing Black women are a “political issue” that goes against their policies.

Erika says "consistency" is what the media should keep in mind while covering stories of Black women who are victims of crimes. "We see mainstream media take interest and hurry to get quotes or publish an article or story while we’re in a news cycle, but once that is over or the interest in a case has subsided, reporters and journalists are no longer seeking out cases of the under-represented," she said.

"True crime as a topic has become an explosive empire with a widespread interest, so if people are consuming these traumas for entertainment, the very least the news media can do is allot a daily or weekly segment on their stations to highlight these stories or to give a platform to grieving families," she concluded.