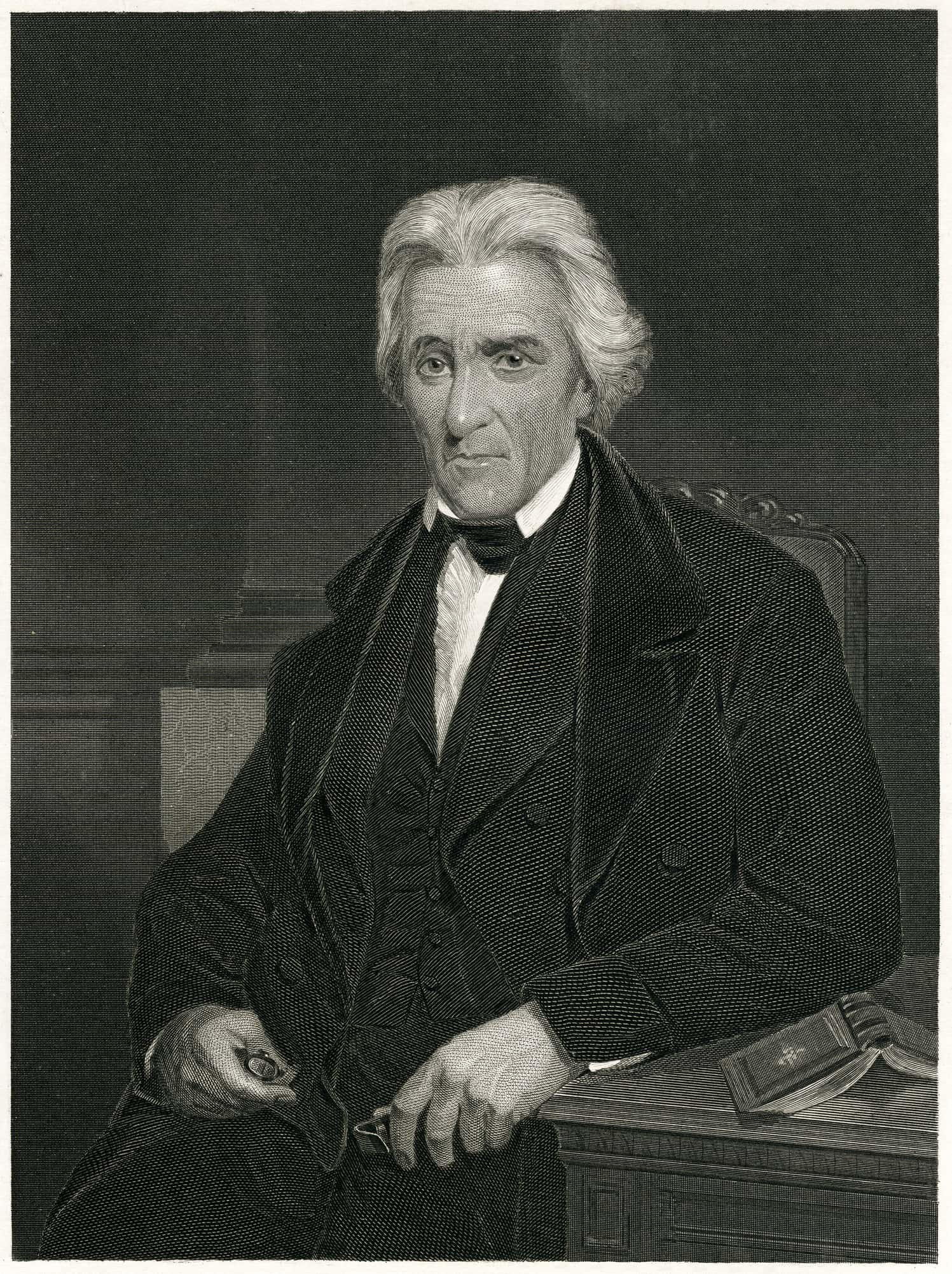

Trail of Tears: Truth behind Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act and the tragedy it inflicted on Native Americans

On 22nd June, protesters gathered at Lafayette Square outside the White House and attempted to bring down a statue of Andrew Jackson that was commissioned in 1847. While police removed the protestors using pepper spray before the statue was taken down, it was vandalized with the words "Slave Owner" spray-painted across it. Previously, it was vandalized twice in 2015 when the phrase "Black Lives Matter" was spray-painted in the first instance and "Justice for D" in the second instance in a reference to D’Angelo Stallworth, who was shot and killed by officers from the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office.

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States whose legacy is marred by one key piece of legislation that led to the forced relocations of thousands of Native Americans that resulted in death and widespread disease among the community. Today, those forced relocations are collectively known as the "Trail of Tears." Read on to know more about the history of the relocations and the locations covered by the Trail of Tears.

The 'Five Civilized Tribes'

For many generations, the lands east of the Mississippi River had been the homeland of five Native American tribal nations -- the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations in the south, and the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations in the west. When the number of white settlers spreading westwards increased, they wanted to use the land for themselves. White Americans often feared and resented the Native Americans they encountered and viewed them as unfamiliar, alien people who occupied lands that the white settlers wanted. Some officials in the early years of the United States tried to "solve the Indian problem" by "civilizing the Native Americans," by trying to make the Native Americans as much like the white Americans by encouraging them to convert to Christianity, learn to speak and read English, and adopt European-style economic practices -- such as individual ownership of land (and sometimes slaves). The Native American nations who embraced these customs and became known as the “Five Civilized Tribes.” However, for many white Americans, this was not enough. This is where Andrew Jackson enters the picture.

Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal Act of 1830

Jackson supported the removal of Native Americans at least a decade before his presidency. As an army general, he had spent years leading brutal campaigns against the Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and the Seminoles in Florida -- campaigns that resulted in the transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres of land from Indian nations to white farmers. As such, the same became his top legislative priority when he became the President of the United States in 1829. In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, which provided the federal government with powers to exchange lands with Native tribes and provide infrastructure improvements on the existing lands. While the Act was criticized by many, including Christian missionaries, Jackson viewed the demise of Indian tribal nations as inevitable, pointing to the advancement of settled life and demise of tribal nations in the American northeast.

After the Act was signed into law, the Cherokee filed several lawsuits regarding conflicts with the state of Georgia -- one of the biggest supporters of the Indian Removal Act. While the Supreme Court ruled against legislative interference by the state of Georgia, Jackson vigorously negotiated a land exchange treaty with the Cherokee, fearing open warfare and a broader civil war. After only a fraction of the Cherokees left voluntarily, the US government, under the presidency of Martin Van Buren, forced most of the remaining Cherokees west in 1838. The Cherokees were temporarily remanded in camps in eastern Tennessee. In November, the Cherokee were broken into groups of around 1,000 each and began the journey west. They endured heavy rains, snow, and freezing temperatures.

By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans had been driven off of their land in the southeastern states and forced to move across the Mississippi to Indian Territory. The federal government promised that their new land would remain unmolested forever, but as the line of white settlement pushed westward, “Indian Country” shrank and shrank. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state, and the Indian Territory was gone for good. The Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chicksaw were also relocated under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. One Choctaw leader portrayed the removal as "A Trail of Tears and Deaths", a devastating event that removed most of the Native population of the southeastern United States from their traditional homelands.

Deaths

Potentially, as many as 100,000 Native Americans were pushed out of their traditional land. Historians estimate that up to 15,000 men, women, and children died en route to these first Indian reservations. Causes of deaths associated with the Trail of Tears vary but include disease contracted while in containment camps awaiting removal or while in new lands post-removal, exhaustion, and/or elements while traveling along the Trail, starvation and/or malnutrition, and battle for those resisting removal.

Walking the Trail of Tears today

The Trail of Tears is over 5,043 miles long and covers nine states: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. Today, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is run by the National Park Service and portions of it are accessible on foot, by horse, by bicycle or by car.