Millions of Americans to face dangerously hot days in coming decades as climate change may shatter heat index

Americans will experience dangerously hot days as climate change will lead to a significant increase in the frequency and severity of extreme heat across the US, a new analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) has warned.

The situation will be so severe that the current heat index will not be able to measure the hot days. According to the UCS, over six million people in the US will be exposed to “off-the-chart” heat conditions by mid-century, up from the current number of 1,900.

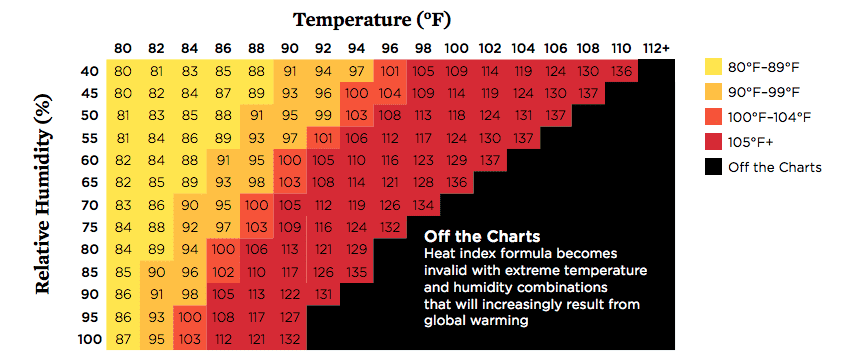

To warn people of anticipated or ongoing conditions that could cause heat-related illnesses or death, the National Weather Service (NWS) of the US combines temperature and relative humidity to produce a heat index, or a “feels like” temperature.

According to current guidelines, NWS issues a heat advisory when the heat index in a region is expected to reach or exceed 100°F for 48 hours, and it issues an excessive heat warning when the heat index reaches or exceeds 105°F for 48 hours.

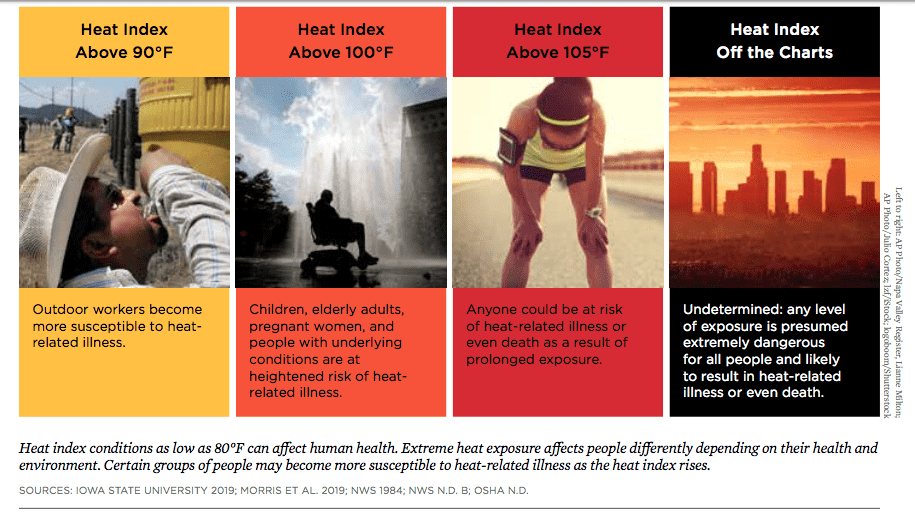

“An off-the-charts heat index is so extreme it exceeds the limits of the NWS heat index scale, which starts topping out at a heat index of 127°F, depending on the combination of temperature and humidity. Off-the-charts days have been rare historically, but this is poised to change dramatically. Countrywide, more than 1,900 people per year have historically been exposed to the equivalent of a week or more of off-the-charts heat conditions; this number is projected to rise to more than 6 million people by mid-century, assuming no population changes,” says the report. It adds, “Any level of exposure to off-the-charts conditions is presumed extremely dangerous for all people. Any prolonged exposure is likely to result in heat-related illness or even death.”

By late century, the number of people exposed to a week or more of off-the-charts heat conditions will rise to roughly 120 million people - over one-third of the population.

The analysis

In this analysis, the researchers have calculated the number of days per year with heat index values above 90°, 100°, and 105°F -- as well as the number of off-the-charts days, when conditions fall outside the range of the current heat index formulation-- between now and the end of the century.

The report also examined three scenarios: “no action,” “slow action,” and “rapid action” to reduce global emissions. The analysis has been published as a peer-reviewed study in the journal Environmental Research Communications.

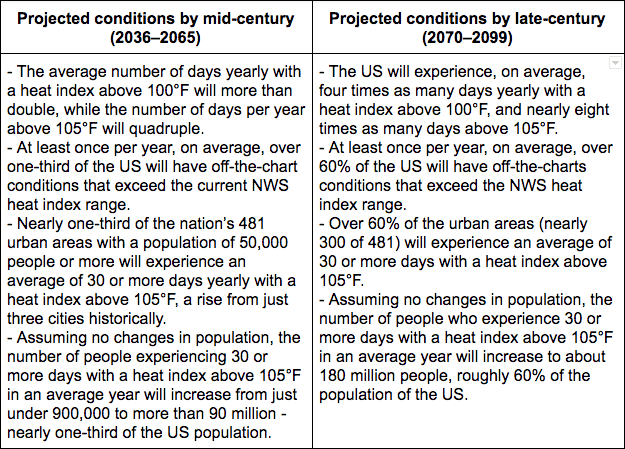

According to the researchers, the average number of days with a heat index above 100°F will more than double, while the number of days per year above 105°F will quadruple, by mid-century.

“If we stay on our current global emissions path, extreme heat days are poised to rise steeply in frequency and severity in just the next few decades. This heat would cause large areas of the US to become dangerously hot and would threaten the health, lives, and livelihoods of millions of people. Such heat could also make droughts and wildfires more severe, harm ecosystems, cause crops to fail, and reduce the reliability of the infrastructure we depend on,” says the team.

The assessment shows that if no action is taken to reduce emissions by mid-century, the average number of days per year, with a heat index above the 90°F threshold, would go up by 70% from a historical baseline of 41 to 69.

The number of days with a heat index above the heat advisory threshold of 100°F would increase, from 14 historically to 36. The number of days above the NWS excessive heat warning threshold of 105°F would increase from five historically to 24.

“Historically, 29 of 481 US urban areas have experienced 30 or more days with a heat index above 100°F. With no action to reduce heat-trapping emissions, that number would rise to 251 cities by mid-century and include places that have not historically experienced such frequent extreme heat, such as Cincinnati, Ohio; Omaha, Nebraska; Peoria, Illinois; Sacramento, California; Washington, DC; and Winston-Salem, North Carolina,” say the researchers.

By late century, the average number of days yearly with a heat index above 105°F would increase eight-fold to 40.

The report also gives detailed regional and state-specific information. The US Southeast region, as defined by the latest US National Climate Assessment, for example, would be the hardest hit seeing an average of 96 days per year with a heat index above 100°F, 73 days per year with a heat index above 105°F, and 12 “off-the-charts” days per year by the end of the century if no action is taken to reduce global warming emissions.

Further, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi will experience the largest rise in extreme heat. In the US Northeast region, Delaware, the District of Columbia, and Maryland will experience the maximum rise in extreme heat, shows the analysis.

Some people will be impacted more than others, says the report. “With the number and intensity of hot days projected to climb steeply across much of the US, millions of outdoors workers already at elevated risk of heat stress - including construction workers, farmworkers, landscapers, military personnel, police officers, postal workers, road crews, and others - would face greater challenges,” the scientists state.

The researchers say timely action could limit the number of people facing frequent, extreme heat.

“The analysis also finds that the intensity of the coming heat depends heavily on how quickly we act now to reduce heat-trapping emissions,” says the team.

Slow action would lead to an average of 18 days annually with a heat index above 105°F, about five fewer than projected with no action.

“With this scenario, over 30 million people would avoid exposure to 30 or more days with a heat index above 105°F, and 84 urban areas would be exposed to that frequency of heat, compared with 152 with no action. These findings show that emissions choices make a difference even in this time frame; that significant changes are still in store; and that faster, more aggressive action to reduce emissions would be needed to avoid those changes,” says the report.