K-Pop Exposed: 'Slave contracts' once ruled the industry, now fans dictate what an idol is allowed to do

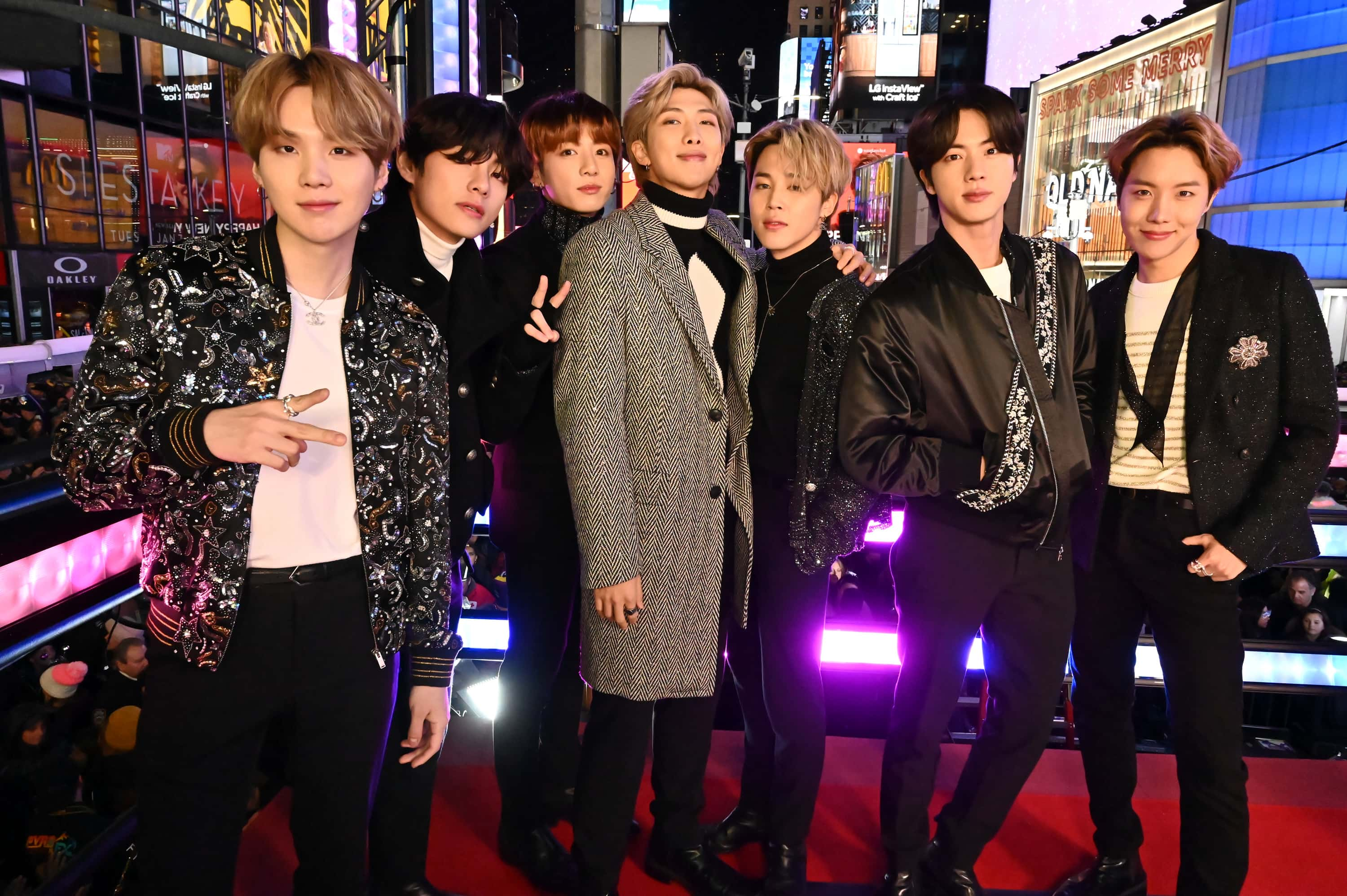

It's impossible in the current era to be unaware of the existence of K-pop. The 'hallyu', or 'Korean wave' that began decades ago has seen aggressive growth over the past few years, owing as much to the international appeal of groups like BTS and Blackpink as to the rising popularity of South Korean culture in general. This boom in the country's exported cultural commodities has led many to presume the purveyors of that culture would see an unmatched level of wealth and freedom. Yet, the actual world of idols contracts and deals isn't quite as rosy as one might be led to believe.

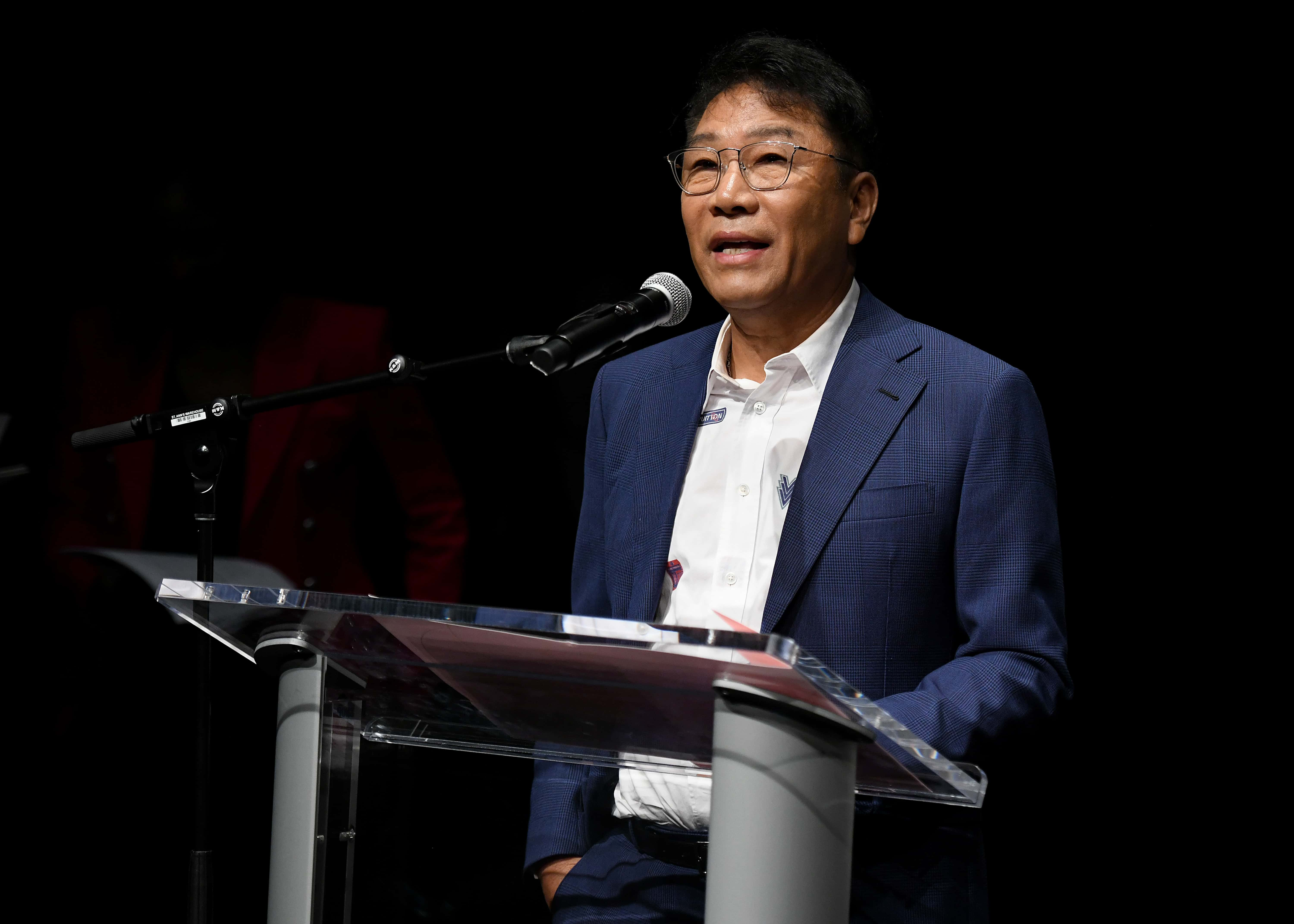

Popular music in South Korea existed long before Lee Soo-man founded SM Entertainment in 1996. But it was Lee's mark on the music industry that essentially birthed contemporary K-pop, ushering in a new generation of idols who would go on to dominate the local, and eventually global markets. The system that Lee pioneered was simple: scout for talent, train them young and debut them as part of an idol group tailored to what was popular. The first wave of artistes to come out from K-pop drew inspiration from Seo Taiji and Boys, who most credit as being the first K-pop idol group as well as being the impetus for a shift in censorship laws in the country. The group also notably pushed past censorship to bring in a more diverse range of musical styles to South Korean pop, thereby establishing the blueprint for the experimental concepts that would follow from groups like H.O.T., G.O.D., Shinhwa, and many more, with some acts like BoA coming in during the later part of this wave and continuing to revolutionize the industry with their feats.

As K-pop took off, more labels were established. But while the 'Big Three' of SM, JYP, and YG were able to coast along thanks to the profits their top artistes were raking in, smaller labels found it significantly harder to break even. Most labels employed a system wherein idols would be required to pay back the cost of their training, which included singing, dancing, and language lessons in addition to living costs, once their work began turning a profit. And in order to maintain the 'image' of the label as well as the persona carefully constructed for each idol, they would be required to sign contracts that stipulated they were to allow their labels to control everything from their diets to their relationships and social lives. Aspiring idols, eager to make their dreams come true, would often end up signing contracts of this nature while they were as young as 12 or 13 years old, with the contracts themselves extending to a period of ten or more years. This system would come to be referred to as a 'slave contract'.

For most fans of K-pop during its infancy, the concept of a 'debt' was as normal as the flashy outfits of the bands entrapped in them. Groups would often speak about the debt owed to their company, and celebrations would ensue when an idol was finally 'debt-free', indicating they had managed to pay back their label and could now start earning money for themselves. For popular idols, this could take as little as a few years, but for others struggling to make their mark, this could go on for much longer.

Over time, however, the 'slave contracts' started seeing backlash as more and more fans began demanding better treatment for their idols, many of whom slept in cramped, barely habitable dormitories and didn't earn enough to buy themselves a meal. But with the pushback, labels were soon pulled up for mistreatment by South Korea's Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) who declared that they were no longer allowed to use the morality clause and other dubious reasons to cancel trainee contracts. This, as it turned out, was yet another way trainees were left with crippling debt, as they were then required to pay back the label despite never having debuted. For those that did debut, profits from their work would go towards their debt. Idols from the 'Big Three' had some leeway, and would actually see some of their earnings, though not much.

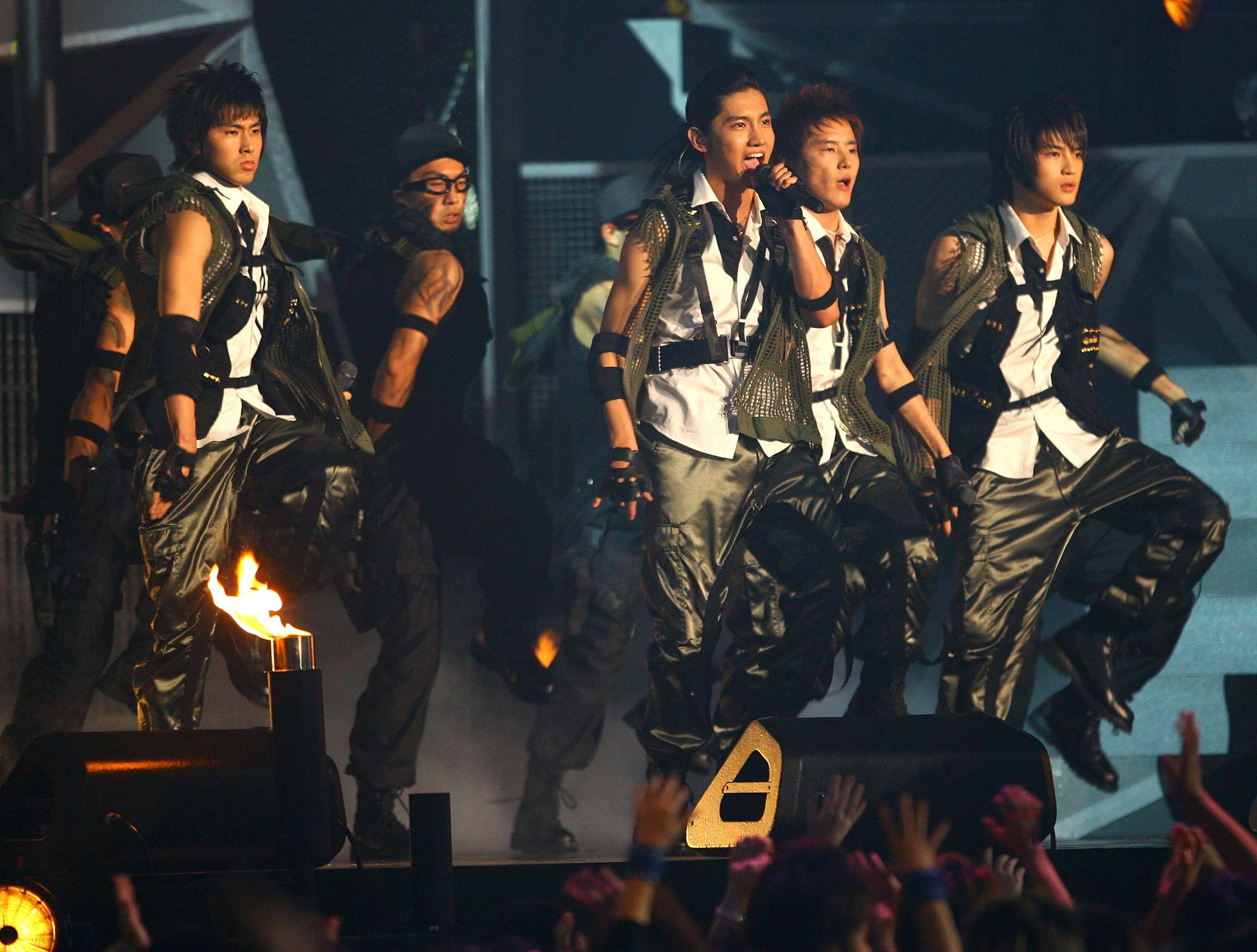

The concept of the 'slave contract' was blown wide open when the group TVXQ sued their label, SM, in 2008, stating their 13-year contract was unfair. The five-member group was the most popular from the second generation of idols, and they helped usher in yet another phase of K-pop, the impact of which continues to be seen in the music and visuals of the industry today. Additionally, this was the phase of the 'hallyu' that put K-pop on the global map. But for all their success, TVXQ was clearly not happy behind the scenes. The harsh working conditions, which included their time being split between South Korea and Japan, paired with the fact that the group saw next to none of their profits were major factors raised in their lawsuit.

The FTC responded by establishing a new rule in 2009 that limited contracts to seven years. They added restrictions to the contracts in 2017, which included reforming the financial penalties for broken contracts with trainees and added clauses that made it difficult for labels to pressure idols into renewing contracts after they expired. Despite the FTC's rulings and industry reforms that followed, idols are still subjected to unfair treatment from labels who continue to control their lives. One case that is often highlighted is that of 4Minute's Hyuna and Pentagon's E-Dawn being ousted from Cube Entertainment in 2018 for the crime of dating one another. Idols are also still subjected to fatphobia and body shaming, with most being forced to diet and exercise and stay under a certain weight. Yet, the conditions are seemingly better now than they were a decade ago. That is, on the management side of things.

In 2014, SM idols Taeyeon of Girls' Generation and Baekhyun of EXO were revealed to be in a relationship. Given the history of idols and management, this should have come as a welcome change in an industry where the artistes' humanity was often suppressed in favor of maintaining an image. Unfortunately, the backlash from fans was swift and harsh. From accusations of it being a PR stunt to the duo being forced to apologize, the hate was relentless. They eventually broke up, and the two groups refrained from interacting much in the years that followed. In 2019, EXO's Kai and Blackpink's Jennie (of YG) faced a kinder response, but still parted ways only a month after their relationship was revealed to the world, stating they were busy with their respective careers. EXO's Chen faced worse when his marriage and impending fatherhood were announced, with some fans launching a petition to have him ousted from the group. And earlier this year when news of Kang Daniel and Twice's Jihyo (of JYP) being in a relationship broke out, netizens began demanding that fellow Twice member Sana refrain from dating, a demand so ludicrous even the group's fandom couldn't help but scoff at it.

Idols now have greater freedom, both in their personal lives as well as their professional endeavors. The pushback from acts like TVXQ has paved the way for younger generation idols to not only have better working conditions but also have a better understanding of what a 'slave contract' is and how to avoid being entrapped by one. Groups like BTS have also helped demonstrate that smaller labels do not need to resort to inhumane methods to turn a profit.

Unfortunately, the incessant demand for a steady stream of content from them from their ever-growing fanbases pretty much locks them inside their studios most of the time, and the backlash for their choices when it comes to romance or friendships is often enough to prevent them from ever having true freedom in that area. And given the split of profits still isn't in favor of artistes, they still do not see most of their profits. Ultimately, while they are no longer bound by the draconian rules of a 'slave contract' and the industry itself has seemingly relaxed its hold on young idols, not a lot has changed from back in the day when idols were overworked, underpaid, and not allowed to live their lives freely.

K-Pop Exposed is a column that gets under the hood of what's happening behind-the-scenes in the world of South Korean pop.