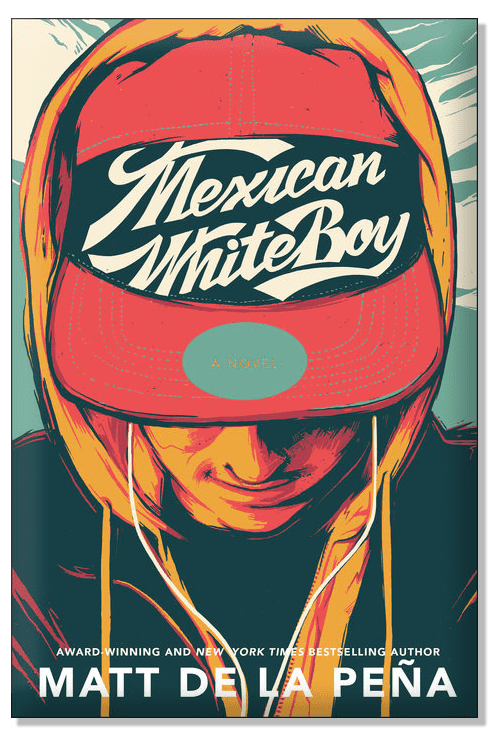

Critical race theory: Why Tucson banned Matt de la Pena novel 'Mexican WhiteBoy'

Matt de la Peña, a New York Times Bestselling, Newbery Medal-winning author of young adult novels, published 'Mexican WhiteBoy' in 2008. It was highly praised. Steve Bennet, writing for the Times, called the book “emotionally rich, a vivid portrait of a So-Cal barrio and its inhabitants.” But there would soon be those who would not see it as such -- but as a tool of a culture war in America.

It’s a story of identity -- and in the case of the book’s protagonist Danny, his half-Mexican identity. “Growing up in San Diego that close to the border means everyone else knows exactly who he is before he even opens his mouth. Before they find out he can’t speak Spanish, and before they realize his mom has blonde hair and blue eyes, they’ve got him pegged,” the book’s dust jacket claims.

READ MORE

Critical race theory: 10 books to read to better your understanding

Racial identity has been a consistent theme throughout writings of contemporary BIPOC authors in the US. And for De la Peña, it plays an important role in his coming-of-age tales, a lot of which are drawn from his own life and experiences -- of growing up in a working-class home under an “umbrella of machismo” with a Mexican father. Stories like his provide representation to young adults who in the not-so-distant past saw only hegemonic whiteness in popular culture and literature.

But in 2012, De la Peña’s book found itself facing a wall it had never expected. On January 1, 2012, after a new state law targeting Mexican-American studies courses that were perceived as anti-White was upheld, it became illegal to teach ‘Mexican WhiteBoy’ in classrooms in Tucson, Arizona. State officials, as per a Times report, cited the book as containing “critical race theory (CRT),” a violation under a provision that prohibits lessons “promoting racial resentment.”

War against CRT

Over the last few months, we have seen Republican lawmakers assert critical race theory is un-American and racist, and argue it will further divide the country, pushing harder and harder to make it illegal in classrooms. Yet, what is un-American and racist in critical race theory seems elusive at best.

The Washington Post’s Philip Bump explained in a recent analytical piece that the phrase, “critical race theory,” has become detached from its original academic meaning. Critical race theory is an intellectual movement and it studies racism at the systemic level, examining how policies, laws, and court decisions can perpetuate racism even if they are seemingly race-neutral. “In popular usage now,” Bump explains, “it refers to a broad mélange of race-related curriculums, claims, and anecdotes.”

As per a report by the Pew Charitable Trusts, legislators in at least 15 states have introduced measures this session that would prohibit the teaching of critical race theory or related concepts in all publicly funded schools, sometimes including penalties such as the dismissal of teachers or defunding of school districts, despite no evidence that it is being taught in any public school.

The report stated that the measures are part of a full-throttle conservative push to restrict discussions of racism and inequity in the name of defending American institutions. A March poll by market research firm Leger and The Atlantic found that 71 percent of respondents had never heard of critical race theory, but 48 percent of all respondents did not think critical race theory should be taught in US schools. It also found that 75 percent were not aware of the controversy in their state regarding critical race theory.

The Pew report also noted something very important: “There is no evidence that critical race theory, as defined by its originators, has been taught in any public school. Nor has a school board in any state cited critical race theory as an element of its curriculum.”

A small victory

But this conservative push to sanitize public education of America’s racial history and present is clearly not new. And what happened to De la Peña’s ‘Mexican WhiteBoy’ is proof of that. Andrew LeFevre, a state spokesman in 2012, said that while the Education Department had found the Mexican-American studies program out of compliance with the law, it was the Tucson district’s job to decide how to enforce the ruling. “I think the district said: ‘Let’s be safe and collect this material. We don’t want a teacher from Mexican-American studies to use it in an inappropriate fashion,'” he told the Times in 2012.

Tom Horne, the state education superintendent at the time and a Republican, accused the district’s Mexican-American studies program of using an “anti-White curriculum to foster social activism”. At the time, the program served 1,400 of 53,000 students in the Tucson district, which is 60 percent Latino,” the Times reported.

‘Mexican WhiteBoy’ fell into a category of books that could no longer be taught but could be used by students for leisure reading. When De la Peña arrived at a Tucson school on an invitation to speak, he donated his fee to buy 240 copies of his books, which he gave to the students. “I want to give back what was taken away,” he told the school newspaper.

In De la Peña’s case, the conservatives did not have the last laugh. A federal judge in Arizona ruled in 2017 that the state violated the constitutional rights of Mexican-American students by eliminating the Mexican-American studies program, saying officials “were motivated by racial animus” and were pushing “discriminatory ends in order to make political gains.”

Students and their parents had sued the superintendent of public instruction in Arizona and members of the State Board of Education alleging that their rights under the First and 14th amendments had been violated when the Tucson Unified School District moved to eliminate its Mexican-American studies program. And Judge A. Wallace Tashima, a US circuit court judge sitting in a state district court, agreed. Tashima said students were denied the “right to receive information and ideas.”