Researchers trace mysterious Fast Radio Bursts (FRB) to source in galaxy 3.6 billion light-years away, will now search for machine source

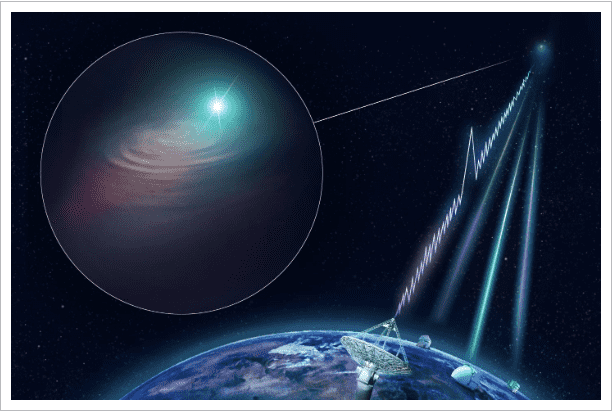

In the first-of-its-kind discovery, an Australia-led international team of astronomers has determined the precise location of a powerful one-time burst of cosmic radio waves, known as a Fast Radio Burst (FRB). The team made a high-resolution map showing that the burst originated in the outskirts of a Milky Way-sized galaxy about 3.6 billion light-years away. This is a major breakthrough as fast radio bursts last less than a millisecond, making it difficult to accurately determine where they have come from.

FRBs, according to the paper, are brief radio emissions from distant astronomical sources. Some are known to repeat, but most are single bursts.

According to an article in the National Geographic, "while astronomers have seen hundreds of these cosmic pulses over the past decade or so, the latest work marks the first time they’ve caught a single burst in action and subsequently pinpointed its origin. In principle, finding out where these so-called fast radio bursts come from should help scientists narrow down the machinery that powers such extreme explosions."

Previously, astronomers had discovered fast radio bursts in 2007. In the 12 years since then, a global hunt has netted 85 of these bursts. Most have been "one-offs", but a small fraction are "repeaters" that recur in the same location. In 2017, astronomers found a repeater's home galaxy, but localizing a one-off burst has been much more challenging.

The latest discovery was made with Australia-based Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation or CSIRO’s new Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope in Western Australia.

The galaxy from which the burst originated was then imaged by three of the world's largest optical telescopes — Keck, Gemini South, and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. The research team developed a new technology to freeze and save ASKAP data less than a second after a burst arrives at the telescope. "This technology was used to pinpoint the location of FRB 180924 to its home galaxy (DES J214425.25?405400.81)," says the paper.

ASKAP is an array of multiple dish antennas, and the burst had to travel a different distance to each dish, reaching them all at a slightly different time. The researchers describe in their paper that from these tiny time differences — just a fraction of a billionth of a second — they were able to identify the burst's home galaxy and even its exact starting point, which was 13,000 light-years out from the galaxy's center in the galactic suburbs.

While the cause of fast radio bursts remains unknown, the ability to determine their exact location is a big leap towards solving this mystery. The researchers explain in their findings that these bursts are altered by the matter they encounter in space. The findings further state now that astronomers will be able to pinpoint where they come from and use them to measure the amount of matter in intergalactic space, that astronomers have struggled for decades to locate.

"Much like gamma-ray bursts two decades ago or the more recent detection of gravitational wave events, we stand on the cusp of an exciting new era where we are about to learn where fast radio bursts take place. Ultimately though, our goal is to use FRBs as cosmological probes, in much the same way that we use gamma-ray bursts, quasars, and supernovae," team member Stuart Ryder of Macquarie University, Australia told the Daily Mail.

The paper was published on June 27 in the journal Science.