Remembering Woodstock: How the Altamont Free Concert ended the hippie era 4 months after pioneering festival

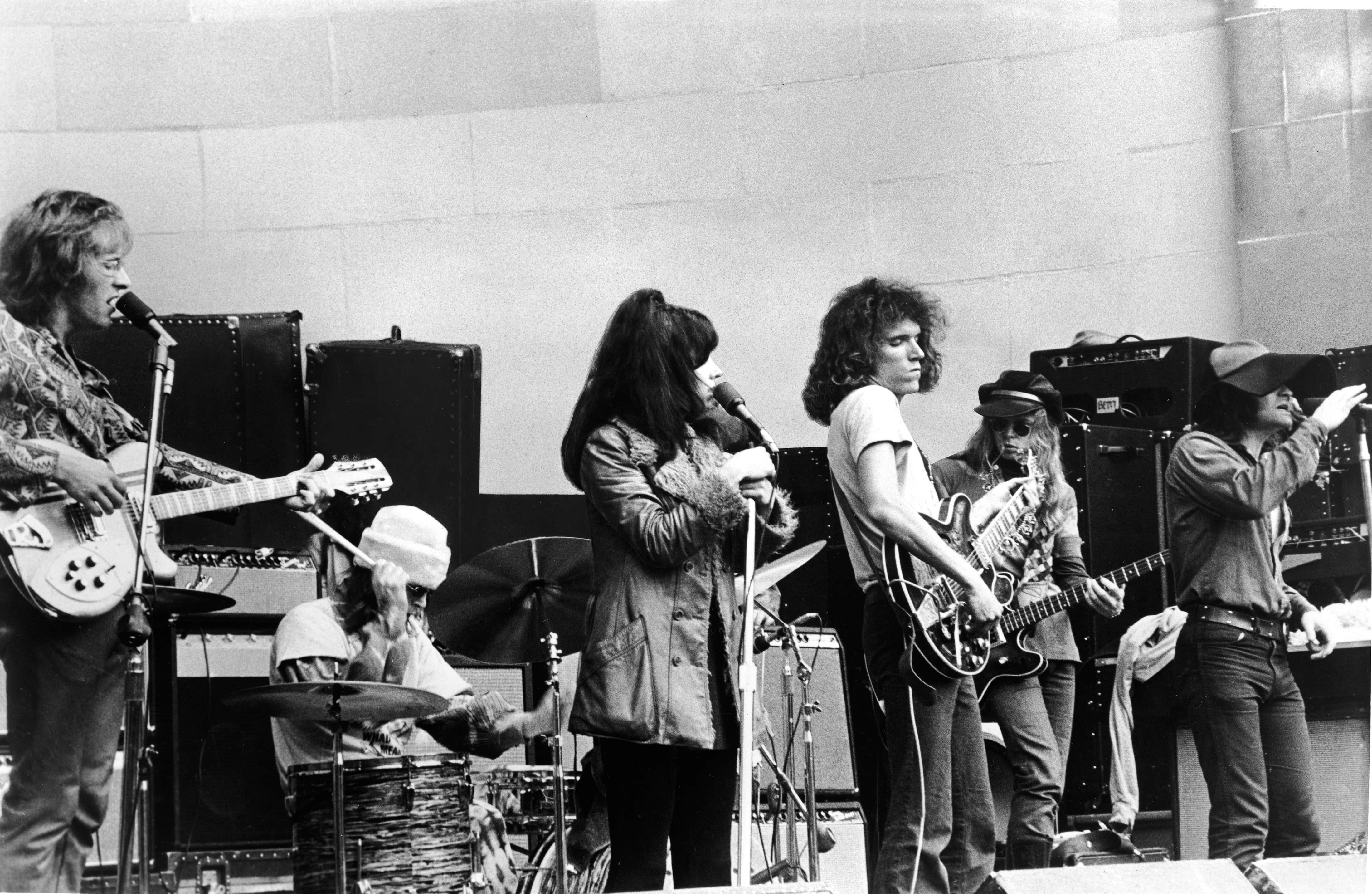

In the years following the iconic Woodstock Festival held in August 1969, many others attempted to recreate the magic of the biggest counterculture music festival ever. But despite the best attempts of several hopefuls, nothing has ever lived up to the original. What exactly made Woodstock so unique, so special, that not even rockstars themselves were able to mimic its glory? Perhaps the answer lies in the Altamont Free Concert founded by the Jefferson Airplane's Spencer Dryden and Jorma Kaukonen, with acts like Jefferson Airplane and the Rolling Stones roped in as headliners. The lineup was promising and the show held less than four months after Woodstock, was attended by over 300,000 people all expecting to be treated to a 'Woodstock West' of sorts. But what they got was the antithesis of everything Woodstock represented.

Dryden and Kaukonen had originally envisioned staging a free concert in Golden Gate Park. They soon set out getting the best rock bands on board, finalizing plans by early December. But the plans soon broke down because of a lack of cooperation from the city and police departments, which many believed stemmed from the clash between the hippie community and the police. Around the same time, the Rolling Stones were preparing to hold their own free concert in San Francisco in response to criticisms that their 1969 US tour tickets were priced too high. The band hoped to secure the San Jose State University's practice field for their concert, at which the Grateful Dead were also set to make an appearance. They were denied. As the bands all scrambled to find a location, they faced several barriers including ideal spaces already being booked and disputes over money and film distribution rights. Finally, Altamont Raceway owner Dick Carter, who had never actually heard of any of these bands, offered his Altamont Speedway in Alameda County as a venue. Out of sheer desperation, Jefferson Airplane agreed.

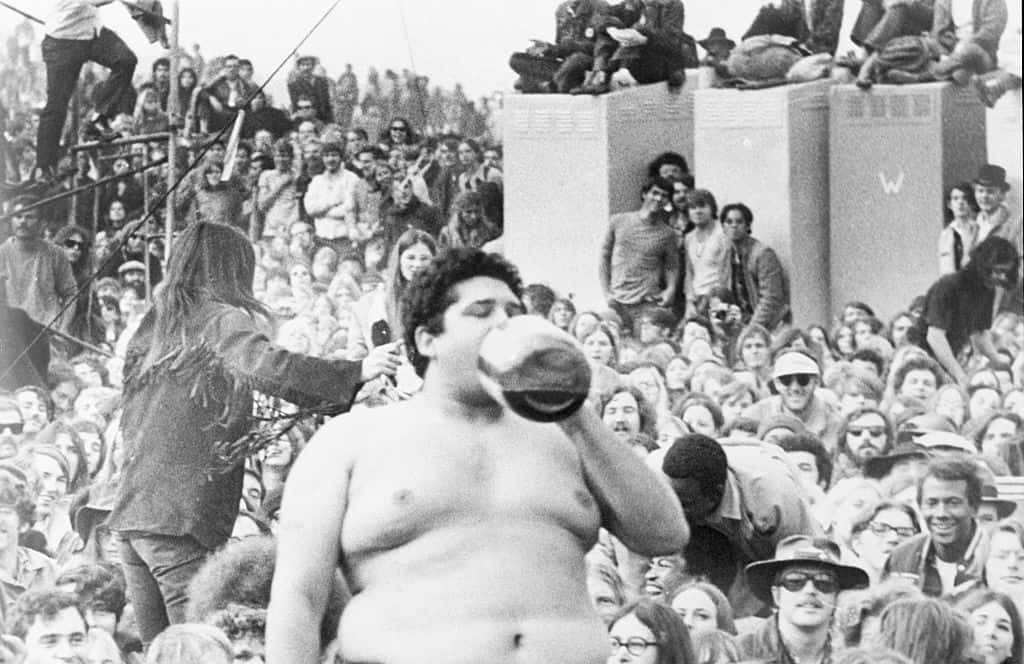

Singer Grace Slick would later state in her biography, "The vibes were bad. Something was very peculiar, not particularly bad, just real peculiar. It was that kind of hazy, abrasive, and unsure day. I had expected the loving vibes of Woodstock but that wasn't coming at me. This was a whole different thing."

The largest issue, it would appear, was a lack of planning. Because of the last-minute shift in venue, the new location at Altamont had no facilities to cope with the massive crowd that would soon descend on it. Additionally, the stage, which had been built to sit atop a hill at Sears Point, was now going to sit at the bottom of a slope, making it too low and potentially dangerous for performing acts. With no barrier set up, it would have been easy for anyone from the audience to simply fall onto the stage mid-concert. To counter this, 17 members of the Hells Angels motorcycle club, led by Oakland chapter head Ralph "Sonny" Barger, were paid $500 in beers to stand around the stage to provide security. According to Stones' road manager Sam Cutler, who allegedly paid the $500 himself and was never reimbursed by any of the bands who were meant to share the cost, the agreement was that the Angels would prevent anyone from tampering with the generators. Angels member Bill "Sweet William" Fritsch corroborated this account to some extent, stating they never agreed to provide security, only to lend a helping hand with things like giving directions. Using the Angels might seem like an odd choice, but the club had provided similar services to both the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane at previous events. There was no reason, therefore, for them to suspect this choice would cause them any trouble.

But once the concert was in full swing, several fights broke out around the stage, with witnesses claiming the Angels were involved in every single one. The crowd, populated by drugged-out concert-goers looking for a good time clashed violently with the Angels, a biker club simply there for the beer and to enjoy some good music. The concert, which started innocuously enough, devolved into a cesspool of agitated mobs, with the Angels using sawed-off pool cues and motorcycle chains to defend themselves. This, according to multiple accounts from the concert organizers and crew, was largely due to the Angels being given little to no instruction on what their actual job was: they were simply given a drink, asked to sit around the stage, and protect the bands performing on it. By that definition, they probably did fulfill their role.

However, the lack of any real security meant several concert-goers were left with severe injuries and in some cases traumatic memories. This included thirty people needing to be airlifted to hospitals owing to severe injuries, including Ace of Cups lead singer Denise Jewkes who, at six months pregnant, received a skull fracture after being hit in the head by an empty beer bottle thrown from the crowd. The Stones would later foot Jewkes medical bill. After one of the Angels' motorcycles was knocked over, presumably by accident, the violence reached a fever pitch. Jefferson Airplane's Marty Balin, who hopped off stage attempting to quell the violence, was knocked out cold by an Angel during the band's set. Band guitarist Paul Kantner's sarcastic note of gratitude led to Angel Bill Fritsch jumping on stage and arguing with him. Both the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones soon left the venue, refusing to play their sets, with the Stones only returning later at sundown to perform, during which Jagger was punched in the head by a concert-goer as soon as he got out of the band's helicopter. Stephen Stills was repeatedly stabbed in the leg by an Angel with a sharpened bicycle spoke during Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's set.

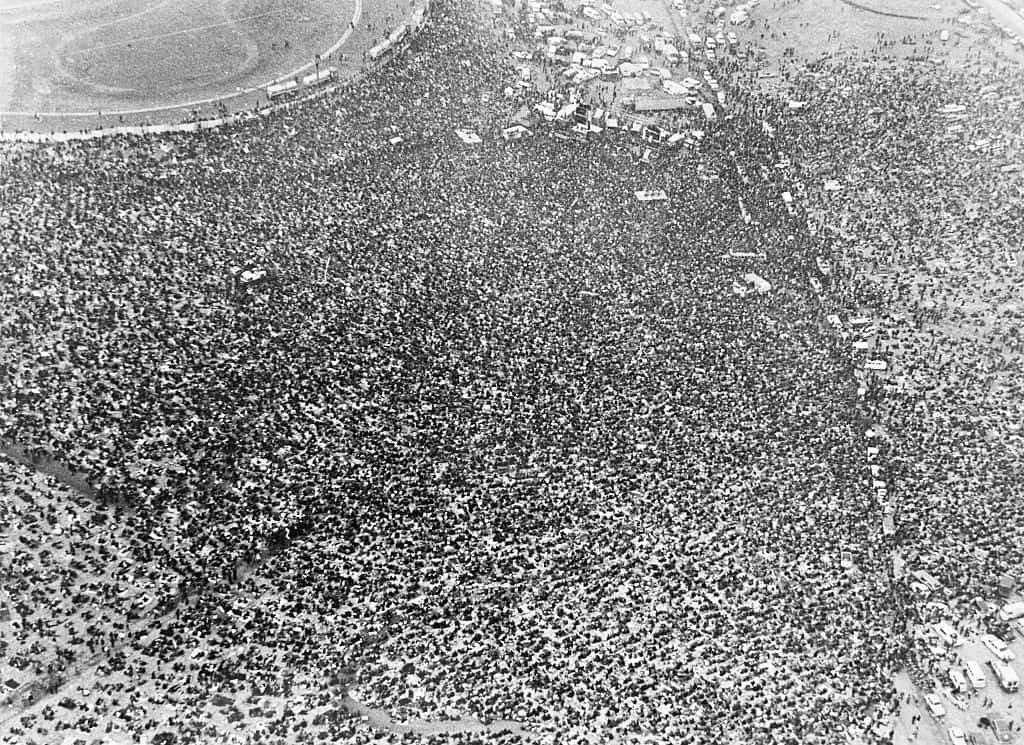

And if the injuries weren't serious enough, three babies were born mid-concert, and four people died: 18-year-old Meredith Hunter, who, following an initial scuffle with the Angels, was later stabbed and trampled to death by them after they spotted him waving a gun during the Stones' performance of 'Under My Thumb', another man who drowned in a canal while on an LSD trip, and two others who were crushed by a runaway car. And Carter, despite hiring 400 guards to protect his 80-acre racetrack property, found it in ruins following the event.

In conversation with SFGATE Carter wryly stated, "Those Stones were a bunch of snot-nosed little kids who didn't know what they were doing. They were just having a ball and playing with the drugs and stuff, and didn't stop to think that you have to do some real planning for something like that." He continued, "They told me we'd have about 50,000 kids there, but I swear there must have been 500,000 by late afternoon. We put in 1,000 portable toilets, 2,000 garbage cans, rented 16 helicopters. But all day long they just kept coming, like ants over the hill."

And therein possibly lays the biggest reason why Altamont failed where Woodstock succeeded and why it would go on to earn the reputation of being the event that signaled the end of the freedom, peace and love espoused by the hippie counterculture movements. Woodstock, despite also struggling with locations, still ensured the event was equipped to handle the nearly 500,000 people that gathered. And where they lacked resources, dairy farm owner Max Yasgur was more than happy to supply some out of his own pocket. Altamont, however, didn't just lack planning. It lacked heart. Where Woodstock was set up to give the youth and the counterculture movement a voice, Altamont was simply designed to be a rock festival that could mimic the euphoria of Woodstock but not its underlying social and political themes.

The Stones earned the harshest criticism for Altamont's failure, with many declaring that the only reason such an ill-planned event went forward was that the band wanted to film their free concert and shut their critics down. The notion that the Stones, and Jagger, in particular, were to blame became even more entrenched in the memories of rock fans and critics alike after a 2008 revelation from a former FBI agent that some Angels conspired to murder the singer in his Long Island home. The agent further alleged it was in retribution for the Stones' concert film 'Gimme Shelter' painting them in a negative light. The club has always maintained that Altamont was the Stones' fault. Jagger has never confirmed nor denied the alleged attempt on his life. And Altamont lives on as the festival that represented the end of the hippie era, a sad moment beautifully encapsulated in Don McLean's iconic song 'American Pie' where the singer, referencing Jagger's Satanic Majesty black-and-orange satin cape sings, "I saw Satan laughing with delight. The day the music died."