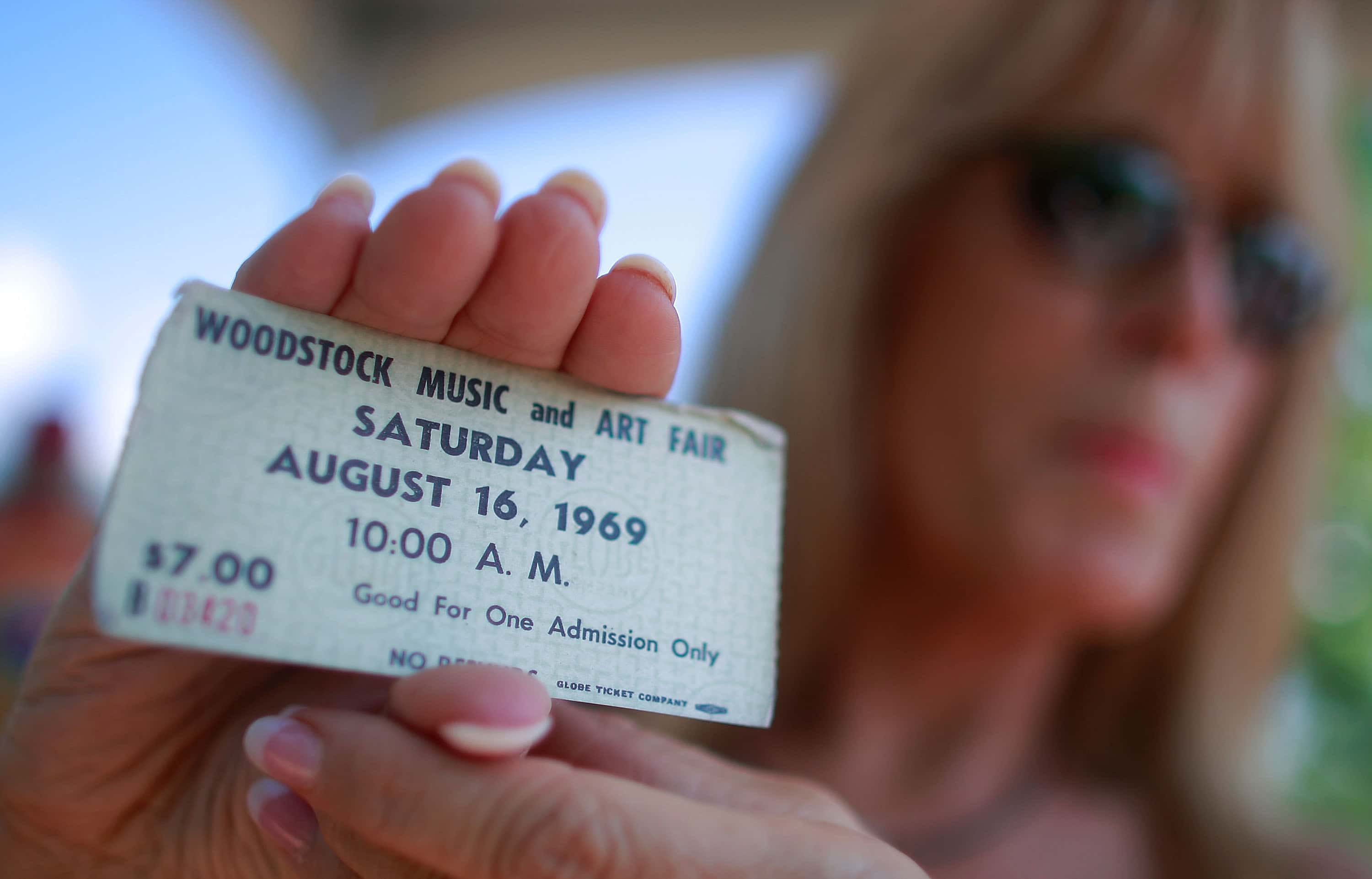

Remembering Woodstock: How dairy farmer Max Yasgur and other heroes saved the Woodstock 1969 music festival

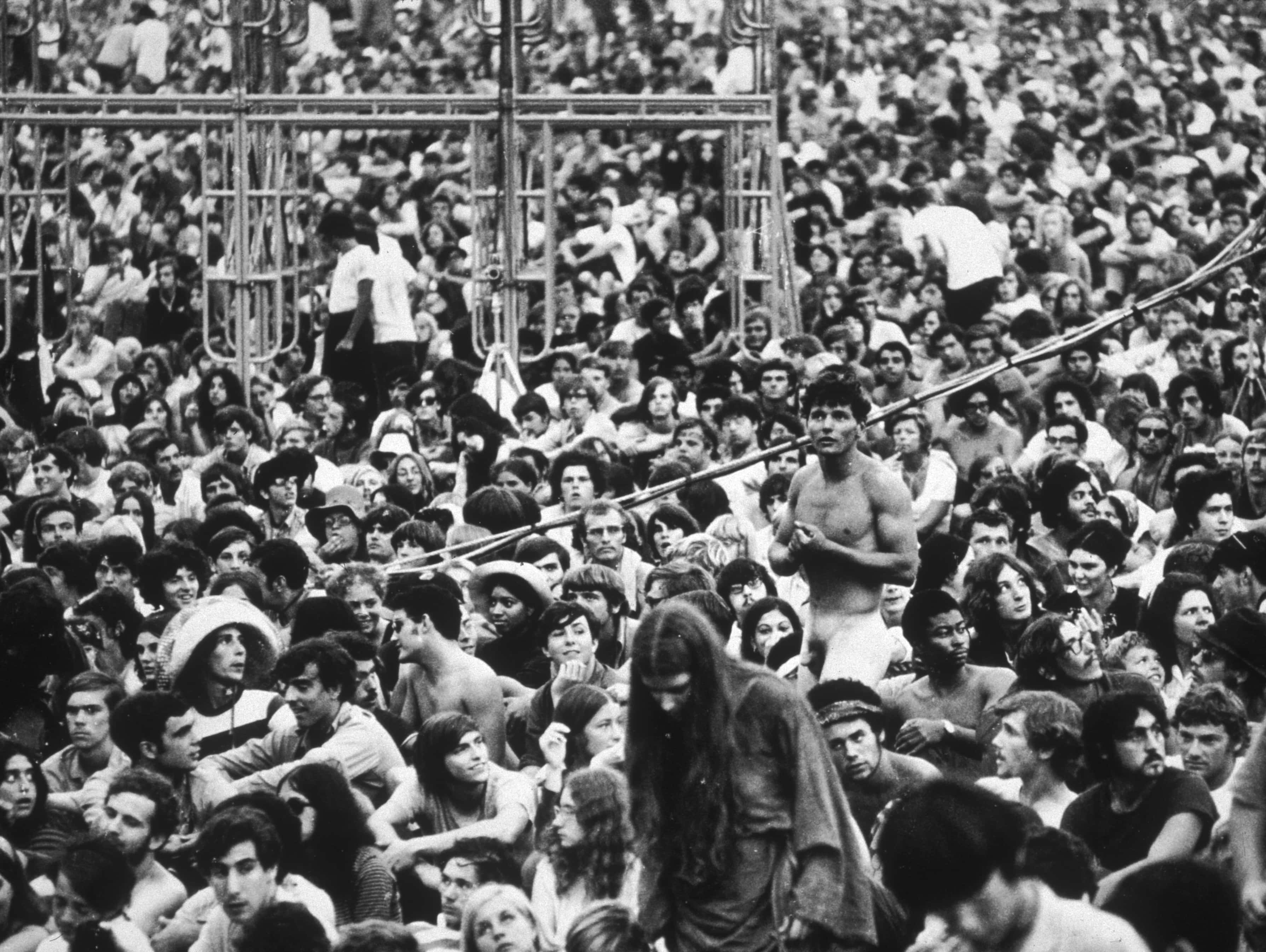

The Woodstock Music and Art Fair aka Woodstock 1969 as we know it today, has stayed in the imagination of music lovers across the globe for more than 50 years. Even today, the influence it exercises over culture and counterculture is considered the stuff of legend. The festival was held at a 600-acre farm in the town of Bethel near White Lake, Sullivan County and attracted a record crowd of 500,000 hippies and music lovers over three days. At the time, in August 1969, America had been at war in Vietnam for more than a decade. Woodstock emerged as a peaceful mass demonstration against the futility of war. A new generation of pacifists soon emerged; a peace and music-loving generation that blossomed in the shadow of post-WWII America.

Now how is it that a quaint town outside of New York would emerge as one of the most hallowed sites of contemporary culture? It's well known that Bob Dylan put Woodstock on the map as he moved into the quaint town (others who moved in were Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Blood, Sweat and Tears). In the counterculture circles, the town came to be referred to as Dylan's turf and his refuge, causing a sort of cultural war between the town's old and new inhabitants. The newcomers fueled an economic expansion vis-a-vis headshops, cafes and folk festivals. However, the newer musical forms and pot-smoking crowd created an unsavory flavor for some of the town's older inhabitants. A chasm emerged between the supporters of the traditional state, the denizens of law and order and the freedom-loving generation reared in the lap of World Peace aka the "flower children" as we refer to them today.

Set against this backdrop, a group of four young men emerged, namely Michael Lang, John Roberts, Artie Kornfeld and Joel Rosenman. Young and rather inexperienced, Rosenman and his trust fund-endowed Roberts put out an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal. Claiming to have unlimited capital, they solicited other young men with “legitimate business ideas.” Lang and Kornfeld joined the duo when their idea for a music studio, recording company, and

rock festival at Woodstock was shortlisted. These ideas would set in a motion a tumultuous journey that culminated at one of the farms of Max Yasgur, the biggest dairy farmer in Sullivan County, New York.

The story goes something like this. Lang at the time was running a headshop in the town of Woodstock. His proposed idea for a concert was rejected by the already embittered townspeople who went to the extent of passing health, safety, and traffic regulations to put a full stop to the plan. The next town to boot them out was Wallkill, where they leased a 200-acre property for $10,000. Once again, the citizens' committee, in cahoots with local politicians, used the law to put paid to the plans for Woodstock.

Notwithstanding these setbacks, the team from Woodstock Ventures, aided by hotel owner Elliot Tiber, pitched to the town council in Sullivan county. This time the team was better prepared and apparently gave proof of a three million dollar insurance policy they had drawn to protect the town from any damages. More confusion ensued between the town and zoning boards due to a lack of clarity about jurisdiction, but the deal was finally struck. Plus, the organizers also found support in the Catskill Resort Association and the Business Association of the town of Bethel, who were looking forward to reviving the local economy. In the end, the unwelcome festival materialized at White Lake village, in Bethel, New York.

From the very beginning, the organizers took measures to offset the antagonism and build goodwill. Woodstock ventures donated $10,000 to the town’s medical center building fund. They then drew up preliminary plans to address issues such as food, water, sewage, and medical facilities that the locals were worried about. Despite the measures adopted by the organizers, the town was still hostile to the idea.

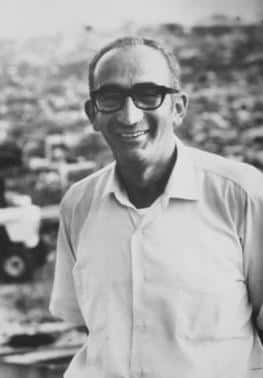

Enter dairy farmer Max, the unlikely savior of the Woodstock 1969 music festival, who gave permission for the concert to be held on his 600-acre farmland in Bethel, New York. Soon after word spread that the festival was going to be held on his farm,Max’s wife remembers how some villagers had put up a sign asking others not to buy milk from her “hippie loving” husband. But Max was unfazed and this bespectacled farmer became the hero the music world didn't know they deserved. Described as a prim and proper Republican, Max believed in individual freedom and the freedom of expression. Facing ostracism from his community, Max stood firm against fellow citizens who were so unsympathetic to the younger generation who were against the war. Some may attribute Max’s support to commercial motives, even the fee he charged Woodstock Ventures for the gig is still a matter of speculation. But what we know is that Max was quite a rich man, he owned over 2000 acres of farmland and had single-handedly built up the family’s dairy business from scratch when his father died while he was still a teenager.

Given the kind of legal hassles that organizing Woodstock entailed, it is interesting to note that Max was a graduate who had studied real estate law at New York University. Moreover, his son Samuel S. Yasgur was an assistant district attorney in Manhattan at the time of Woodstock. These facts suggest that Max had the wherewithal to stand up for what he believed was right. His short speech onstage on the second day of the festival reflected his belief and respect for the younger generation and what they wanted to prove to the world.

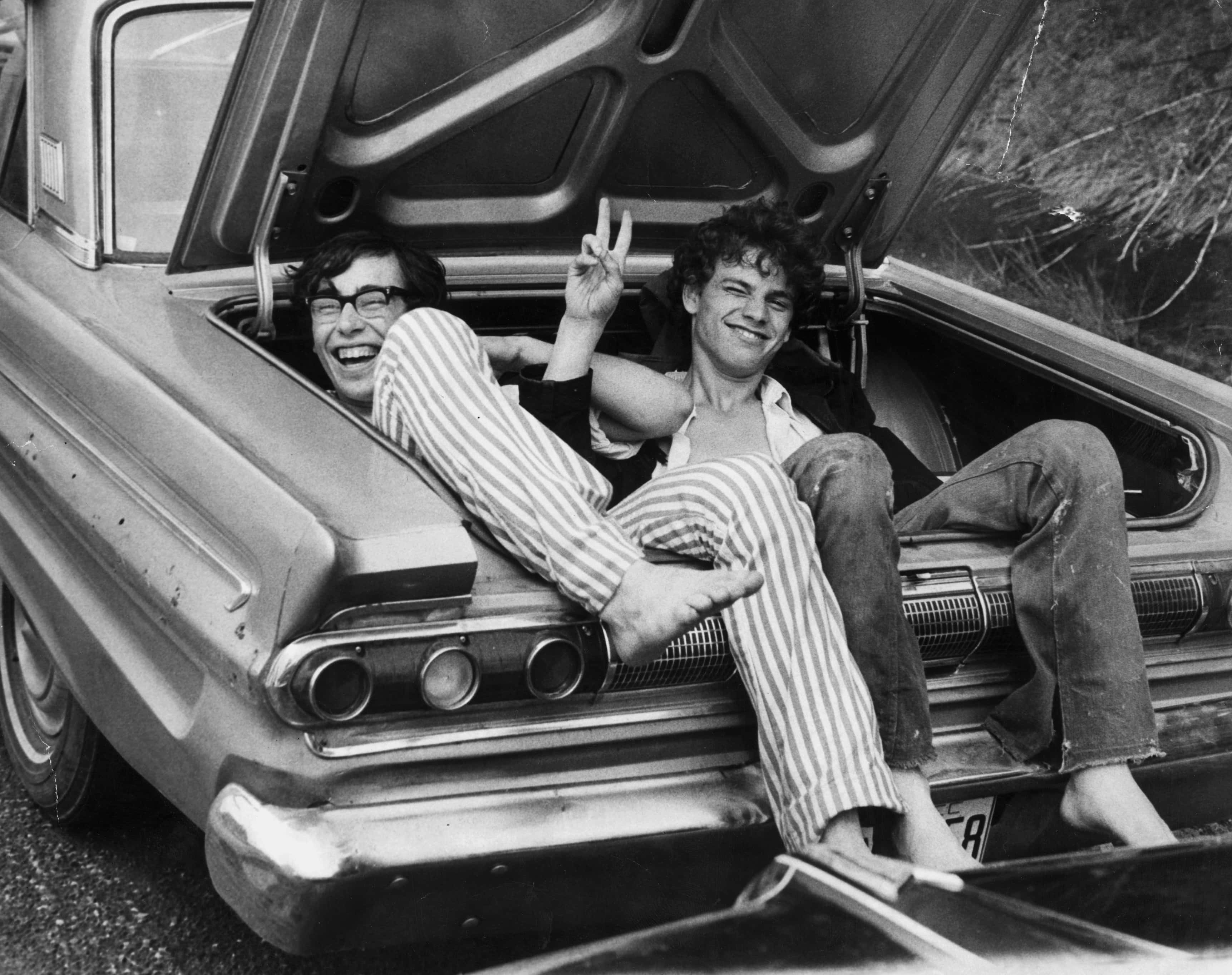

What Max probably saw can be succinctly expressed in the words of Max Lerner, that “these young revolutionaries are on their way... to slough away the life-style that isn’t theirs... and find one that is.” So while Max's memory still remains in the hazy shade of counter-cultural history, he was not the only one who helped make history, there are many other unsung heroes. When Woodstock finally began on the August 15, roadblocks were aplenty. The off-duty New York policemen hired by the organizers to man the crowds were denied permission by their police chief and then the 100 buses which had been hired to ferry concert-goers didn’t show up. What ensued what a chaotic traffic jam beyond everyone’s expectations. Concert goers abandoned their cars and hitchhiked to the farm. The supply lines for food, equipment and medical supplies were stalled and a concert for 50,000 people saw over 500,000 people arrive.

The unexpected number of crowds threw everything into turmoil. Soon there were food shortages, villagers even started selling drinking water, accommodation was insufficient and security scarce. Nevertheless, the spirit of the new generation was such that there was no significant case of violence reported. Despite their doubts, local citizens and policemen were surprised that the young hippies were so well behaved and courteous. Turning the tide, local citizens began to warm up to the crowds and thousands of hard-boiled eggs were gifted by the local farmers. Max and his family donated cheese, butter and bread besides free drinking water and other dairy products like milk.

The Hog Farm, a commune in New Mexico flew in 100 of their volunteers, who dished out hot meals of rice, oatmeal and bean soup. The Women’s Group of the Jewish Community Center in Monticello made 30,000 sandwiches, served by the Sisters of the Convent of St. Thomas. Once the flow of luck shifted course, help started coming from the most unlikely of sources. For instance, helicopters from a nearby airbase flew in several sorties to bring in emergency supplies. Knowing that drugs were to be consumed at the festival, law enforcement didn’t exhibit high-handedness, knowing that excessive force could result in riot-like violence. And so, in the end, both sides in the ensuing cultural war had come together like the two sides of a coin. Braving all odds stacked against it, Woodstock 1969 survived, and in retrospect, thrived, in the imagination of many music lovers who still walk the earth today.