'Hanna's War' Book Review: Daunting love story of female physicist who made atom bomb possible in WWII

The day the US dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima, a New York Times report stated: "The key component that allowed the Allies to develop the bomb was brought to the Allies by a ‘female, non-Aryan physicist.’” Many years down the line when Jan Eliasberg came across this paragraph she wondered who this woman was? What is her story? And why has she been robbed of recognition in the pages of history while her scientific colleagues won the Nobel Prize for atomic fission discovery?

The woman was a genius Jewish-Austrian physicist Lise Meitner. She became the inspiration for Eliasberg’s eponymous reimagination of the last months of World War II in her novel ‘Hanna’s war'. The 230-page edgy novel is socially and politically charged with undercurrents of racism and antisemitism, male chauvinism, sexism, cultural purity, American aristocracy and fundamentalism that make the narrative unassailably powerful.

Set in 1945, during the last months of World War II, Dr Hannah Weiss was a remarkably gifted physicist. She is removed from her ongoing work in top-Secret 'Manhattan Project' at the Los Alamos National Laboratories in Mexico, USA, where a team of scientists are racing against time to crack the heart of the atom before the Nazis. However, Hanna is suspected as a spy working secretly for Nazis in helping them make the bomb that has the potency of mass extinction or can power cities if in the right hands. She is interrogated extensively by Major Jack Delaney from military intelligence who tries to unearth if she is really passing scientific inputs for the bomb to the Nazis.

Author Eliasberg has granted a kind of agency to Hanna that exudes confidence, scientific brilliance and moreover “self-determination”. It is with this sagacity that she never lets the interrogator Jack outwit her. In fact, her catalytic persona immerses Jack in self-introspection and reveals certain truths about his real identity to the reader.

As the probe continues, the author moves back and forth in time. She reveals some startling truths of sexist and racist views prevalent in the top echelons of the German scientific community. Eliasberg uncovers how scientists do not want to credit a Jewish woman for the great scientific discovery that later led to the making of the atom bomb and disparage her findings as “Jewish Physics". However, they publish her findings but give sole credit to Hanna’s colleague Stefan Frei with whom Hanna worked day and night on the atomic fission discovery.

At this juncture, Hanna maintains her prestige and refuses to be mentally enslaved by bigoted cultural purists. She is passionate about science and cares nothing of the honors she has been robbed off. Her sensitive, emotionally loving, and highly guarded nature wins her lovers too. However, there is an enigma around her that permeates throughout the novel. Is Hanna protecting someone out of love? Who is he? Is she a spy working for Nazis? Where does the morality of scientists and world powers stand when they have weapons of mass destruction? These pivotal questions get answered in the end as the novel blasts certain truths about its characters before the final bombardment of Hiroshima takes place.

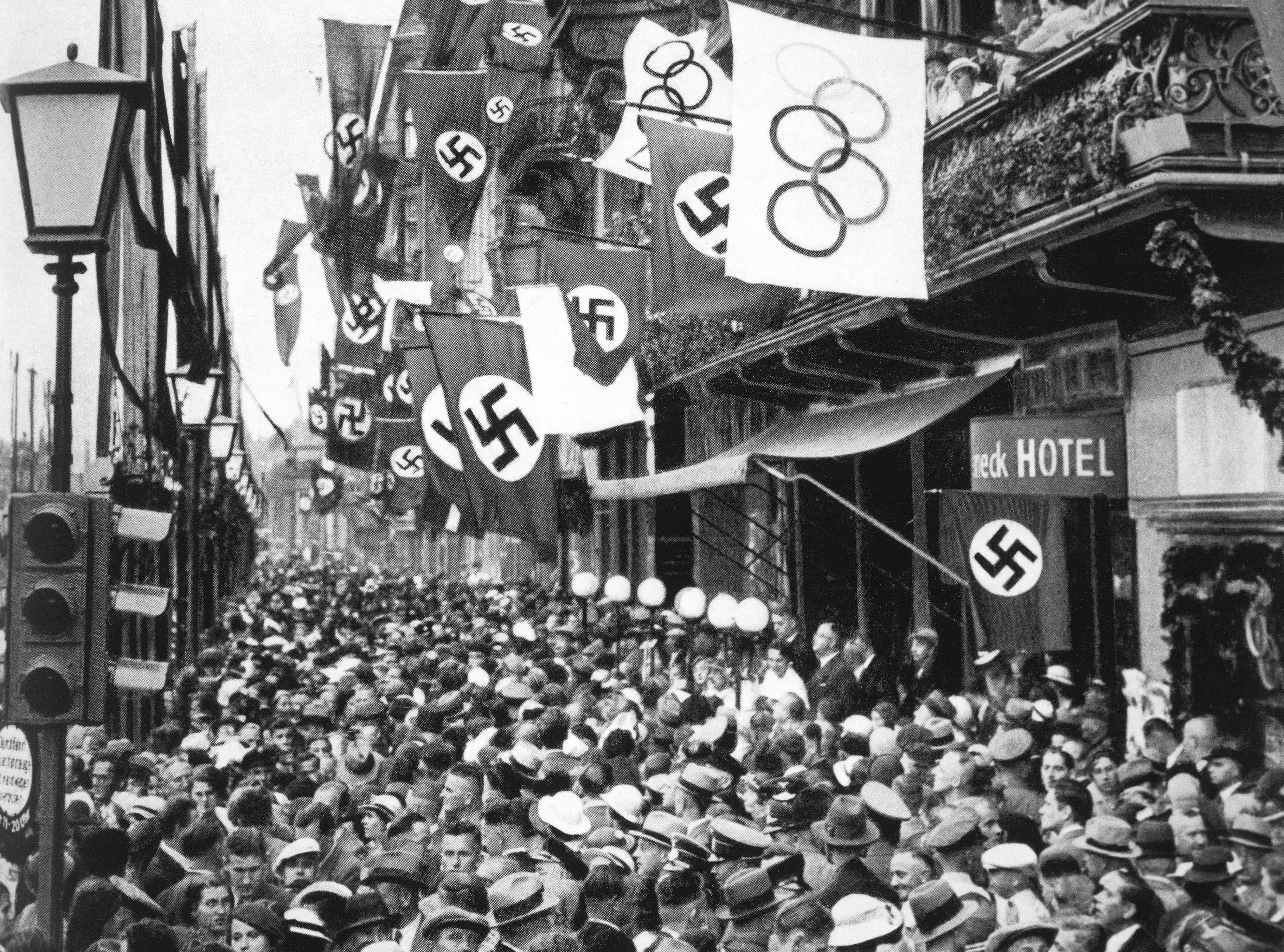

As a war novel, Eliasberg also encapsulates the bone-chilling horrors of Jews fleeing Germany, their rapes under Nazis, the fanatic kind of romanticism with patriotism and nationalism, the mass annihilation of Jews in ghettos and camps, and their prohibition from public spaces. However, what makes this story unique is it's not the victimhood of Jews that overpowers the narrative. Rather, the author renders them various shades. They are young rebels (Hanna’s cousin), mature and open-minded (Hanna’s uncle), emotionally vulnerable (Jacob), and strong and independent (Hanna). They bear the socio-political consciousness of their times and face them in their distinct ways.

The writing of the novel is like a screenplay where one can imagine the exact scenes. The novel is indeed poignant, gripping, crisp, quick-witted and sentimentally nerve-racking, rendering it a daunting love story buried in the harsh reality of the final days of World War II where the truth is uncovered with a humanist vision making it a must-read.